Retro-Futurist Artist Laurie Simmons: Still Waiting, Still Playing, and More Spectacular Than Ever!

Retro-Futurist Artist Laurie Simmons: Still Waiting, Still Playing, and More Spectacular Than Ever!

It’s the stuff of artists’ most epic dreams and wildest fantasies. There may even be a psychedelic drug - some mushroom, microdot, or synthesized compound - that could mimic the experience of taking it all in - whether as its creator or as a devoted admirer of the artist like me. Decades of artistic vision and evolution are collapsed and concentrated into a mesmerizing, three-minute video that incorporates the latest AI technology, projected on the towering screens of the largest outdoor digital gallery in the world. For the artist, it must feel like a living hallucination. For the countless thousands looking up, it’s one of the most Instagram-worthy moments ever. I wasn’t lucky enough to be in New York City during Laurie Simmons’ “Midnight Moment” which ran from December 2024 to January 2025, but I’ve taken the long-form journey - following the (r)evolution of this retro-futurist artist for forty years - watching as she’s built, expanded, and reimagined her signature themes with range, risk, and a haunting sense of continuity.

Laurie Simmons - Autofiction: Moving Pictures, Waiting & Looking Up

Thanks to my interest in Simmons, I learned of something I had never known existed and am now slightly obsessed with. Every night at 11:56p.m., Times Square begins a screen countdown - ten seconds when the world’s largest everything bagel of humanity comes to a halt. At 11:57, the ‘Midnight Moment’ begins: three minutes when more than 90 synchronized billboards drop their sales pitches and become an unfathomably large, glowing gallery of digital art, stitched together into one collective flicker of imagination. A few months back, that flicker belonged to Simmons and her new work, “Autofiction: Moving Pictures, Waiting & Looking Up.” In the film, AI-generated women are spied waiting - hovering somewhere between memory and invention - like scenes from old films you only think you remember. One of the most remarkable aspects of the film is, in an ironic coincidence, how very “of the moment” this “Midnight Moment” feels.

Laurie Simmons On Her "Midnight Moment"

"I don’t think I really got what Midnight Moments was until I arrived at the scene. In fact, I didn’t even want to go to the reception because it was at midnight, and I didn’t want to stay up that late. And also, I didn’t want to invite my friends because I didn’t want them to feel any pressure about coming out at midnight. Finally, I let a woman in my film group know that I had this Midnight Moment coming up where my work was going to be in Times Square, and the women in my film group had been together for really a long time, and were all really close, and she put the word out and suddenly, everyone wanted to join me and come. So we all met for drinks and snacks first, and then we went out in the rain - we were all in raincoats, and we looked up at Times Square to the hundreds and hundreds of ads. My husband was there and he said, “Which screen is it going to be on? How do we know where to look?” And I thought - boy, is he in for a surprise! And then a few minutes before midnight, every single screen in Times Square, I think it was around a hundred, lit up with my video which was called Autofiction and all my friends started screaming, “Look over there! Look over there!” “Laurie! Laurie! Look! Look! LOOK!” And it was like being with a bunch of kids watching the fireworks. It was really an amazing experience!"

I refer to artist Laurie Simmons as a “retro-futurist.” Her film “Autofiction” - itself a term that fuses two opposing ideas, autobiography and fiction - perfectly encapsulates why. Saturating every frame, you feel it - the unique emotional textures - the moods - that all of Simmons' art famously elicits. While artists of every skill level, genre, and category of notoriety are wrestling to determine what AI means to them, Simmons has figured out exactly how to leverage it. Rather than losing her sense of self in the art she creates by collaborating with AI (a tremendous fear for many artists today), she flipped that script on its head. Technology hasn't made Simmons's new work feel like AI - she has made AI feel like Laurie Simmons. This is an artistic achievement that deserves its own special "Moment" of recognition and admiration, separate from the (already enormous) fanfare over her latest works.

What is new and captivating is the way her subjects, now incorporating AI, are like Schrödinger’s models - simultaneously there and not. That has been the message that Simmons' "stand-ins," her dolls, have been silently screaming for decades: "I'm here! I'm not here!" The women in “Autofiction” appear eerily lifelike and undeniably synthetic - present yet intangible. The subjects exist in a liminal state, hovering between real and constructed, authentic and imaginary. She focuses on homes and AI-generated women inhabiting slightly off-kilter spaces (one of her stylistic fingerprints) that blend design elements from decades past with styles from the ultra-present, all rendered in color-drenched dreamscapes. Even in their latest incarnations, Simmons' women are clearly still waiting.

What I find astounding is that despite the virtual light years of sophistication between the AI text-to-image platforms she now collaborates with and the well-used simple tools with which she began, the resulting imagery feels like a remarkably natural progression. I imagine there are thousands of people whose first exposure to Simmons' work came during her month-long run in Times Square for her “Midnight Moment.” Yet, you can step into the world of Laurie Simmons’ art at any point - in any decade since the 1970s - and her work still feels fresh, current, and culturally important in both style and content. Experiencing the collaboration between Laurie Simmons and text-to-image AI is the art world equivalent of the Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga duets - a meeting of legacy and innovation that somehow just makes perfect sense.

The mind-bending aspects of being an artist who began by creating miniature worlds with ironic juxtapositions of scale - photographed using simple techniques - and decades later finding yourself in Times Square, seeing your art every which way you look, cannot be overstated. People all around Simmons are coming and going, but in a personal achievement sense, she has arrived - again and anew, in an undeniably major way that is both retro and futuristic!

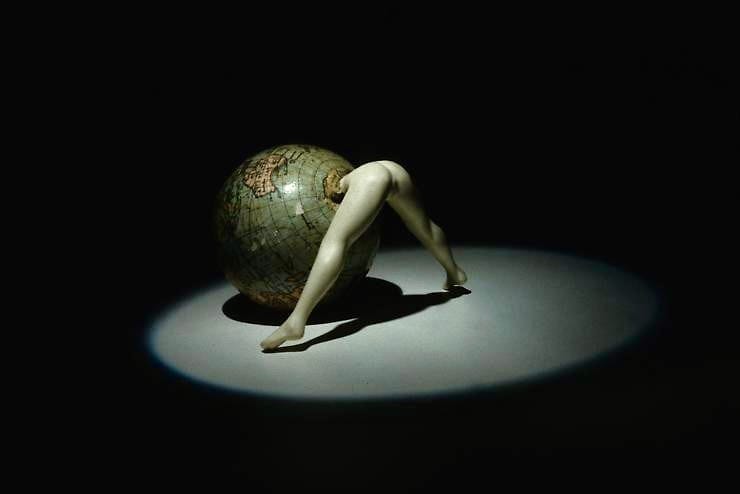

For more than five decades, Laurie Simmons has dug into our collective psyche and pulled forward emotional states and dormant moods by creating tightly-controlled worlds with props. Sometimes they are miniature ones in shoebox-sized dioramas, other times, pocket-sized objects blown up to surreal proportions and adorned with human legs that dance across a stage. The meals in her miniature kitchens are always pot luck style - the viewer brings their own metaphorical dish. She set her tables - sometimes in an almost literal way - with simple, emotionally charged objects that jostle the viewer’s mind, freeing up their own intuitive interpretations about the work’s deeper meanings. For me, it as though the dust of sleeping memories and feelings is suddenly shaken loose, behaving like iron shavings clustering onto a magnet - that magnet is Simmons art. I first fell in love with her work because she catapulted forward into my consciousness the fear and rebelliousness I experienced when, as a young women, I watched my mother perform the role of 1970s housewife and mother - a prisoner in a tastefully-upholstered jail. And she understood.

Gender roles and identity were baked into the family unit when I was a teenager, and though the options for women and non-binary people have broadened considerably since the 70s, the default food chain still positions straight, white men at the top. This antiquated concept continues to underpin our society, like the crumbling Greek columns of the Acropolis. Much of the progress we have made as women as well as Queer people seems to have been written with disappearing ink. Recently, we went back to check the receipts, and they are no longer in the register.

A sampling of images from multiple projects of Simmons' spanning decades

Simmons’ work is focused on a few recurring themes that are as resonant and provocative today as when she started: waiting, gender, identity, and regret. Whether you have been following Simmons’ work since the 70s like I have, your first exposure to her work was one of the countless posts of her “Midnight Moment” on Instagram in 2025, or you started engaging with her art somewhere in the decades between, she has probably conjured a storm in your mind made of thoughts and memories you rarely access. She speaks in a unique and magical language that many of us intuitively understand, in my case, right down to the punctuation.

I recently had the absolute pleasure (and pinch me moment) of chatting with Laurie Simmons. I wanted to talk with her not just about her newest work, but about the themes that have followed her - and us - for decades

JONI: I’ve picked out themes from your work that I’d like to talk about. You’ve talked about it quite a bit over the years, and it is definitely a core theme in “Autofiction: Moving Pictures, Waiting & Looking Up” - the idea of waiting.

LAURIE: Right. Right.

JONI: What are we waiting for?

LAURIE: We're waiting for something different in every phase of our lives which is so sad. Because when we're children, we're waiting to grow up, and, you know, be released from our captors, otherwise known as our parents.

There's an urgency when you're a teenager, and you feel like you're living in the wrong house, in the wrong place, in the wrong time. To grow up is so profound, and it feels so real, and then you fast forward to a later stage of your life. You know, where I am now, and all you're thinking about is, “Am I waiting to die?”

- [LAUGHS] -

I mean, when is it going to happen? How is it going to happen? How much time do I have left? And then there are the smaller waitings - the way we were indoctrinated into as children - there were always waitings. Waiting to meet your love, waiting to find out if you'll have a career, then waiting to find out if you'll be successful in your career. And when I was a young artist, I was waiting to know if I should move forward. I remember asking my husband, who was my boyfriend at the time, “Will, I know when it's time to give up?” So I was waiting to know if I should give up.

The theme of waiting, when I used it in “Autofiction” - my way of portraying it - I was thinking about everybody on their phones. Texting or meeting people online and waiting for those 3 bubbles to come up. “Is she gonna text me back? Is he gonna text me back? Are they gonna text me back?”

And this waiting to know - it's a very big theme of mine along with regret. Regret is also kind of tied in there somewhere, but that's another theme that's come up in my work.

JONI: Let’s talk about that theme - regret.

LAURIE: Okay. The notion of regret. I think my mother was always wondering - if we did one thing - like if we went on a little vacation and we picked a hotel. She always wanted to take a car ride and look at the hotel we didn't pick. That seemed very - it seemed very normal to me.

JONI: Wow - that's an interesting way to view things.

LAURIE: I have a book on my bookshelf - it's like this thick [indicating a very thick book with her hands]. It was published in the eighties about regret. It’s when regret was technically, clinically named as an emotion. It wasn't always - there was hate and love and jealousy - and regret wasn't always in that soup of emotions, defined as such. And you know, the essence of regret is - it’s about the road not taken - and there's so much romance there.

The movie "Roman Holiday" where Audrey Hepburn is a princess who runs off and falls in love with a reporter, but she pretends to be a commoner, and then in the end returns. I've seen that movie so many times. In the end she returns to the throne and has thrown away the possibility for love, and has to live with this decision.

As a child and as a young woman, I really romanticized the idea that there were two ways that lives could go, and that if you made one choice, that by making one choice you were always giving up something else.

And that is a crazy way to live your life.

JONI: I never really thought about it in that way. It is kind of a crazy way to live your life, but also a fertile theme for exploration.

LAURIE: So to choose a path, and then really ruminate on the path not taken, and what might have been, that became a theme in my work. It's always been a theme in my life, but that became a theme in my work, and the movie that I made in 2006 is called “The Music of Regret.” It’s a 3 act musical.

The Music of Regret (with foreign subtitles)

JONI: Yes! I’ve seen it and loved it! It’s brilliant!

LAURIE: So that's that's my thing with regret.

JONI: I’d like to talk about the theme of identity in your work. And it's extra interesting because I'm sure that you've had to think about identity in new ways as the parent of a trans child.

LAURIE: I think that my subject from the moment I picked up a camera was the specifics of gender, and especially as that was enacted growing up and living in a 1950s household. And I often tell this story - I had an older sister, and then I was born, and then my mother got pregnant again, and they were really wishing for a boy. And so the baby's room was painted light blue. And then a girl came home from the hospital, a little baby girl, my sister Bonnie. And it was such a subject. Everyone that visited the new baby, my mother, the joke of painting the room blue, and then having to repaint it pink.

And these kinds of things, like what boys could do and what girls could do, and how extremely gendered certain activities were, and clothing. And for a little girl who was rough and tumble, and was called a tomboy - I was always questioning this stuff. It just seemed so weird, and there were no girls in my neighborhood to play with. So I ended up playing boy games, which was fine with me. And I never really loved playing with dolls. I was so ADHD and peripatetic. I would just cut their hair off or cut their heads off. You know, I couldn't do the little fine motor movements. I had great motor skills for drawing, but I couldn't do the fine motor skill things of combing their hair and putting little ties around it and putting their little shoes on. It was not for me.

JONI: I was the same way. I had one doll that I loved, though, and it's what I call ChatGPT now, which was Chatty Cathy. Do you remember Chatty Cathy?

LAURIE: I totally remember Chatty Cathy, and I'm sure you could find the commercials for her all over Youtube.

JONI: As I said in my memoir, she could have been a toaster as far as I was concerned. I loved the idea that you could put the little record in her back, pull the string, and she would talk. She could have been a toaster for all I cared. I didn't care about the doll aspect.

LAURIE: No, it's really about those amazing technological feats. I like those too.

JONI: One of the things I want to talk to you about has to do with my obsession with brains and how they function. I have certain things that I just keep going back to, and some of the things are consciousness and free will and that kind of stuff. And are you familiar with the idea of panpsychism?

LAURIE: Yes, I think my husband's really into all of these philosophies, and we've discussed it. But can you jog my memory?

JONI: So in a nutshell - it's the theory that everything in the universe has consciousness.

LAURIE: Yeah.

JONI: I watch endless YouTube videos about consciousness and all this kind of stuff. The reason I wanted to talk to you about that is because when I watch these, I always think of your art. That's not what the physicists and philosophers are thinking of when they talk about it 🤣, but I do. I think of you putting the legs on inanimate objects. I think of “Dance Of The Severn Handbags.” I think of a lot of what you do - it’s turning inanimate objects into beings that perform.

LAURIE: Right.

JONI: And I just wondered how you think about the idea of consciousness in inanimate objects. I know it's a big idea, but I wonder.

LAURIE: That's a great question. I think it emerges from my childhood and living in Great Neck, Long Island until I left when I was 17 and really never went back. It just informs everything, you know. It's still the sort of fertile territory and rich ground for everything that I make. I've always been able to access really early memories. And I think the desire to have the objects and toys and things around me have life, to be sentient beings, and move and talk, - it was so strong. I remember it. I remember feelings in the middle of the night. I was terrified in the middle of the night, thinking that I could see either the animals or the outlines of things in my room actually moving.

And of course I was a Jewish girl from Great neck so we didn't really celebrate Christmas, but I knew that there were all of these movies on television about how the animals talked at midnight on Christmas. So I’d try to wait up to see if my dog Cindy would finally be able to talk to me. I assigned consciousness to things that didn't have it - bugs, animals. Let's say higher consciousness - we don't know how high their consciousness is, but at least…

JONI: But it's consciousness of some sort.

LAURIE: Yeah, consciousness. But I wanted plants and animals to have verbal skills. I wanted to be able to communicate with them. And that was true of everything around me, and I watched a lot of cartoons that probably were made before I was born. They're silent cartoons, some of them, where they have weird music. I sat in front of the TV and just watched endless cartoons - they're knives and spoons and forks and plates, walking and running, and you know there was a lot of that kind of imagery.

JONI: Another topic that I’d like to chat with you about is control. I read that the scale of your work, especially your earlier work, was all about control. I can related because I loved the idea that I could control everything in front of my camera. When I was a kid, I can remember hard boiling a dozen eggs - I just went to the refrigerator, and I thought eggs were a cool shape, and I hard boiled them and peeled them. I made planets out of them. And you know, just thought they were a cool thing, and I could control this kind of other world in front of my camera.

LAURIE: Right, and you probably got the same feeling that I did that when you looked through the lens it created - a kind of tunnel or stage. That you're creating this world just by blocking out everything around you and magnifying what's in front of you.

JONI: Yes! Exactly.

LAURIE: It is very much like the consciousness of a child - that ability to hyper focus when playing. You know, I always remember that I said it to my mother, and my kids said it to me - “Don't bother me. I'm playing!”

The importance of that - like I'm telling you what playing is, and I'm telling you don't bother me because I'm playing. And think about how enormous that is to you as a child!

JONI: Yes! Absolutely!

LAURIE: So that activity, as an adult, you don't get credit for. Maybe now, as we get more psychologically astute. But you don't get a lot of credit for playing as an adult, you know.

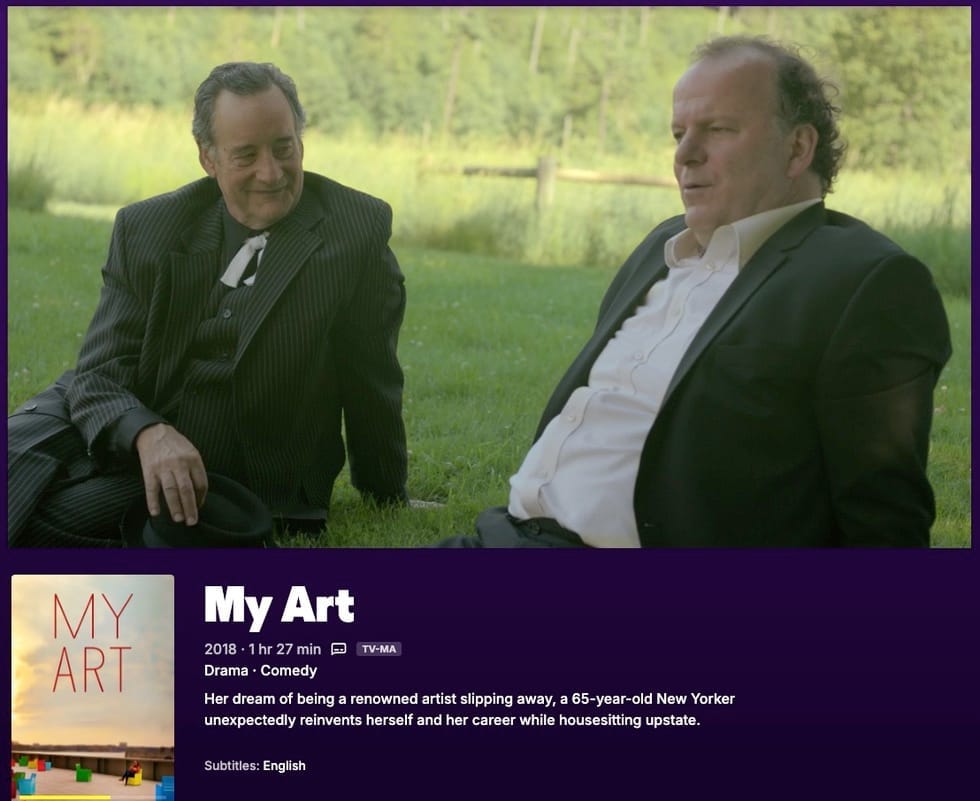

JONI: I’d like to talk about one of the core themes of Joyful Queer. The Mission of Joyful Queer is to boost joy by inspiring resilience, creativity, and connection. Can you talk a little about the scene in your movie, “My Art,” where the guy who plays the wealthy lawyer and the guy who plays the groundskeeper are sitting outside and talking.

The lawyer says: “You know, if I could have been a French actor, I never would have been a lawyer. I didn’t have the guts to follow my bliss. But you, you’re such a good actor, Why’d you quit?”

The Groundskeeper says: “Oh I didn’t quit. I just took a break, you know, things happened. I might get back into it. I’m starting to get the bug again, you know. We’ll see. But you. You’re a big trial lawyer. The Spencer Tracy, Gregory Peck types huh?”

The lawyer says: “Made a little money but I didn’t have this, you know? I mean the joy of these last few days.”

The Groundskeeper says: “Yeah, it’s fun, isn’t it?”

The lawyer says: “Yeah, it’s fun!”

JONI: Can you talk to me about that kind of joy - that comes from creativity?

LAURIE: He's admiring the actor for doing what he loves to do in that the scene. I sort of generalized about the way so many people from my generation, or even my father who was creative, couldn't even imagine living. You know, it takes a lot of guts to lead a creative life. It really does, still.

And I just thought about these two guys, so different. And how that creative experience for that buttoned up lawyer - it suddenly tore everything open for him to just play. That was like the whole aspect of playing again.

JONI: Indeed!

In Simmons’ work, memory isn’t just preserved - it’s remodeled, reimagined, and projected back at us. Whether on a gallery wall or 90 glowing billboards in Times Square, her art continues to ask what it means to look, to wait, and to be seen. She has spent a lifetime creating a sprawling maze of memory palaces and funhouse mirrors. The vastness and volume of Simmons’ work is beautifully organized on her website, www.LaurieSimmons.net.

Laurie Simmons On Activism:

"I’m part of a group called FUTR which stands for Families United For Trans Rights and we worked very hard to get Sarah McBride elected - the first seated trans Congresswoman. She represents Delaware and is just an incredible person. And the thing about being trans is that all of this becomes so personal because people need to meet and understand that trans people are humans like you and me, and they are not just an idea, and they’re not people to be afraid of or to be discriminated against. It’s horrifying, the kind of rhetoric that’s out there now that’s anti-trans, and how much money the Republicans put towards that in their ad campaigns leading up to the last election and even what has transpired since. It’s so excruciatingly painful."

I think the key to activism right now is to find the thing that really has some meaning to you personally, because honestly, there’s so much out there that needs to be fixed. For me, it’s always been women’s reproductive rights - I’ve supported Planned Parenthood. I’ve supported a lot of organizations in the art world that needed fundraising, but I have a trans son, so it’s really obvious to me that this is an issue that I need to wrap my arms around right now, as do so many people. Trans people are less that 1% of the total population, and for those people to be targeted is really painful. And we’re all the trans population in the sense that once they go after them, they’re coming after us, as we all know.

Laurie Simmons is an internationally recognized artist. Since the mid-70s, Simmons has staged scenes for her camera to create images with intensely psychological subtexts and nonlinear narratives. By the early 1980s Simmons was at the forefront of a new generation of artists, predominantly women, whose use of photography began a new dialogue in contemporary art. Her work is part of the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, The Whitney Museum of American Art, and The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City; The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles; The Philadelphia Museum of Art; among others. In 2006 she produced and directed her first film, "The Music of Regret", starring Meryl Streep, Adam Guettel and the Alvin Ailey 2 Dancers. The film premiered at The Museum of Modern Art. Her feature film "My Art" premiered at the 73rd Venice Film Festival and Tribeca Film Festival in 2017. Simmons lives and works in New York and Connecticut.